STATEMENT OF TEACHING PHILOSOPHY

In college-level English courses, reading and writing function as homework. Students usually complete what Lewis Carroll nicknamed “Reeling and Writhing” outside of the classroom, often begrudgingly in library carrels or at dorm room desks. Students read and write to prepare for what they learn and discuss in class--or so I assumed. Yet, my years spent studying oral culture have reminded me that reading is not necessarily silent, nor solitary: reading, be it in the twenty-first-century classroom or the nineteenth-century hearth side, can be communal, loud, lively, and fun. In my courses, we explore what it actually means to read, write, and think together. Yes, this sometimes means performing Shakespeare soliloquies in the melodramatic style of late eighteenth-century elocution guides. (Boy, do students writhe.) But this also means facilitating classes in which students know and listen to each other--in which other students’ ideas, opinions, and responses constitute a crucial part of the semester’s course materials. My courses, then, prompt students to consider themselves as one part of a diverse and dynamic community of readers.

|

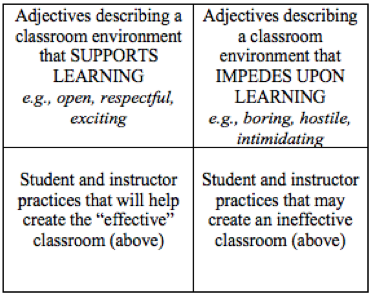

We Make the Rules Collectively: On the first day of class, I facilitate an activity that my colleagues have since termed the “Nesbit Squares.” I divide the board into four quadrants and ask my students to brainstorm ideas to fill each quadrant based on the guidelines pictured. We end up with a list of student and instructor practices that, in many ways, resemble the classroom policies and expectations detailed on my syllabus. Students acknowledge that, in order to create a classroom that is “respectful” and “exciting,” they must, for example, prepare for class, participate daily, and avoid texting during class. But, instead of portraying classroom policies as a set of strictures imposed on students, this approach presents ground rules as practices promoting the classroom that we have defined and envisioned together.

|

We Play: I take seriously the value of goofiness. I wear all of my clothes backwards to introduce back-editing and reverse outlines. I teach poetic form through my “Verse Olympics”—during which the “Poetic-Meter Dash” and “Figure (of Speech) Skating” are always favorite events. We hold a “Top Chef” competition: students judge sample introductions (hors d’oeuvres) and conclusions (desserts) and identify the best “ingredients” for each. A playful classroom, however, is not an easy classroom, nor is it necessarily a lighthearted one. When we hold presidential elections for the characters of Dracula, for example, campaign advocates for the novel's Transylvanian Count and its working woman, Mina Harker, raise questions about how xenophobia and sexism play into both our classroom’s and our country’s electoral politics. Play can crack open the conventional classroom in a way that makes room for challenging questions, as well as for inventive responses.

We Look and Listen Beyond the Classroom: I craft syllabi and assignments that ask students to think in unfamiliar ways about writing and its relation to the communities around them. One of the major essays in my rhetoric course, for example, requires students to identify a moment in which they “wish they’d said something” and contextualize that moment within a debate or conversation in the public sphere. One semester, a student emailed me several months after the assignment to tell me that she had experienced another “wish I’d said something” moment, but, inspired by our assignment, she had said something. She crafted a written response (complete with MLA-cited quotations!) and sent it to the person who had offended her. She was proud of both her writing and her courage in standing up for a personal conviction. As she wrote, “I finally took something I learned and put it to use in the real world.”

I encourage students to allow their lives to change our course and our course to change their lives. I encourage this because I want them to be invested in my class, but, more importantly, because I am invested in them beyond my class. So, we read, write, and, yes, sometimes reel and writhe together as preparation for our course’s true “home” work: to leave at the end of the semester using what we have learned to better recognize and engage communities outside of our classroom’s walls.

We Look and Listen Beyond the Classroom: I craft syllabi and assignments that ask students to think in unfamiliar ways about writing and its relation to the communities around them. One of the major essays in my rhetoric course, for example, requires students to identify a moment in which they “wish they’d said something” and contextualize that moment within a debate or conversation in the public sphere. One semester, a student emailed me several months after the assignment to tell me that she had experienced another “wish I’d said something” moment, but, inspired by our assignment, she had said something. She crafted a written response (complete with MLA-cited quotations!) and sent it to the person who had offended her. She was proud of both her writing and her courage in standing up for a personal conviction. As she wrote, “I finally took something I learned and put it to use in the real world.”

I encourage students to allow their lives to change our course and our course to change their lives. I encourage this because I want them to be invested in my class, but, more importantly, because I am invested in them beyond my class. So, we read, write, and, yes, sometimes reel and writhe together as preparation for our course’s true “home” work: to leave at the end of the semester using what we have learned to better recognize and engage communities outside of our classroom’s walls.